Over the past decade, which has almost paralleled the development of smartphones, a notable trend has been that many hardware functions can now be achieved through software iteration. Previously complex hardware functionalities are being replaced by software that is easier to update and repair, while more advanced features are being integrated. This "wave after wave" substitution trend is also evident in today's hardware development.

However, using software to realize hardware functions has clear drawbacks. Compared to traditional hardware implementations, software tends to be slower, consumes more energy, and offers weaker security.

Nevertheless, since not every new process node delivers significant improvements in power and performance, chip manufacturers often resort to software methods to enhance certain aspects of performance and functionality.

This approach is particularly evident in many applications, especially in data centers, where performance demands are immense. "Moore's Law is slowing down," said Kushagra Vaid, an infrastructure engineer at Microsoft Azure. "It's noticeable that CPU release cycles are gradually lengthening. Design bottlenecks inevitably arise when dealing with CPUs. At this point, as original designs reach their peak, performance faces challenges, and the cost per transistor continues to rise. This forces people to seek new ways to solve problems. In cloud computing, there are numerous scattered workloads that are difficult to run efficiently on general-purpose CPUs."

For the cloud computing industry, reliance is not solely on hardware or software but on software-defined hardware to achieve specific functionalities, which mainly includes the following points:

First, this demand brings customers closer than ever to mobile chips and hardware design, with chip manufacturers becoming more involved in end markets—more so than at any previous time.

Second, achieving a specific requirement often necessitates co-design of hardware and software rather than relying on just one. This means hardware and software must evolve simultaneously.

Third, cloud computing demands emphasize personalized design over universal hardware design.

Finally, the needs of the cloud computing market have led to significant strategic shifts for chip companies and system design firms.

"Based on these factors, many companies will determine their software needs before selecting the required processor," said Bill Neifert, Senior Director of Market Development at ARM. "What we see is that these manufacturers truly consider what they need, what they aim to achieve, and then choose the final processor based on these requirements."

A major constraint in these choices is performance. Ironically, for ARM, its primary characteristic is low power consumption. Thus, in design, we find that processors for specific applications are often low-power processors with defined power limits. "Those making these choices typically do not opt for high-end processors," Neifert explained. "They might choose more advanced processors and then modify the software to achieve better application-specific hardware. So, a trend we're observing is that many manufacturers are using smaller processors and optimizing software to handle multiple tasks simultaneously."

It's important to understand that software efficiency is crucial because no single processor can handle over a hundred programs simultaneously. In many cases, handling three or four programs at once is sufficient.

This perspective is well-reflected in the development of the entire semiconductor industry. "You'll see chips with different performances and workloads being adopted across various applications," said Anush Mohandass, Vice President of Systems Marketing and Business Development at NetSpeed.

In the future, more chips will emerge for image processing, SQL, and machine learning. For different applications and workloads, chip manufacturers will use different chips or design and customize chips based on these specific applications.

More Markets, More Choices

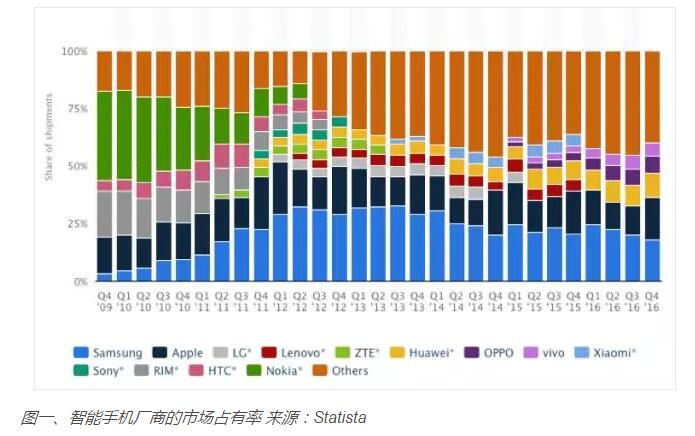

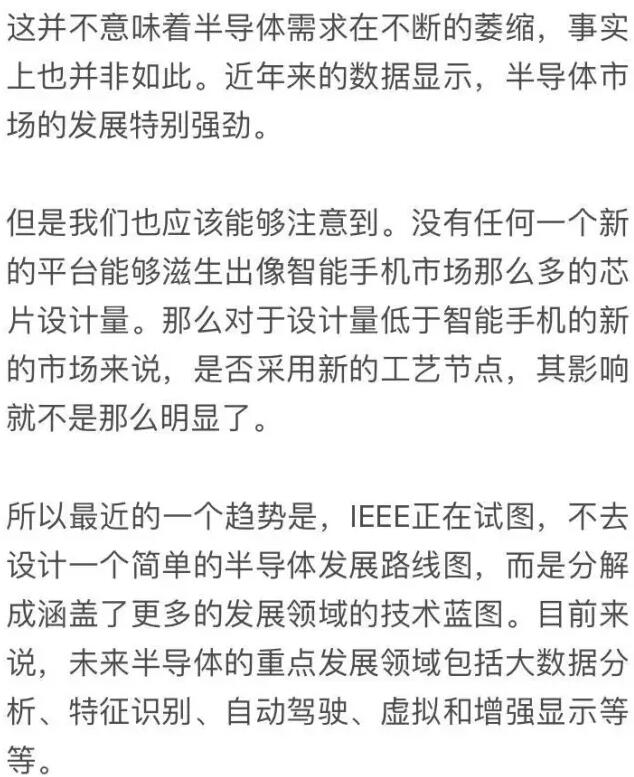

The foundation of these market changes is the significant transformation occurring in the semiconductor market. Historical experience shows that no new platform can design and drive billions of chip sales using a single processor. The same holds true for the mobile chip market, where Apple and Samsung dominate the high-end smartphone segment. In the mid-to-low-end market, numerous smartphone companies like Huawei, OPPO, Vivo, and Xiaomi employ different mobile chips.

Detailed development roadmaps are crucial for different applications and will greatly propel the advancement of these new applications.

"For applications like mobile and infrastructure, performance must be emphasized," said Lip-Bu Tan, President and CEO of Cadence. "In these fields, process technology will advance from today's 10nm to 7nm and even 5nm in the future. However, these areas also face challenges: performance, power consumption, and cost will increase with process advancement, while the pace of development slows and costs inevitably rise. So, recently, many companies have questioned whether transitioning from 16nm to 7nm is necessary, as they haven't seen significant performance and power improvements that would boost their business. Or they might skip certain nodes. Conversely, what drives chip companies to adopt more advanced processes is the timing of new products and applications and the specific requirements these have in terms of development cycle, performance, and power. It can be said that for these companies, multiple approaches can achieve the same goal."

IP Limitations

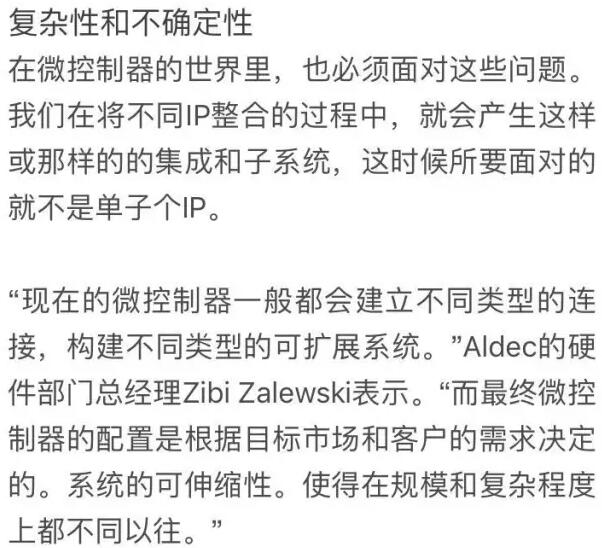

On the other hand, it's important to recognize that developing the next node also involves addressing IP availability.

Developing new technology nodes often means creating new IP. For chip manufacturers, developing IP on the most advanced process nodes is very expensive, with uncertain outcomes and high risks. Sometimes, achieving the same goal may involve entirely different processes, such as using different IP for a specific process.

Additionally, the design process at the most advanced nodes is often highly complex.

"You need ultra-high-performance IP, whether it's modules or interfaces, and you also need to determine what qualifies," said Mike Gianfagna, Vice President of Marketing at eSilicon. "This is part of deciding whether to scale up. You must prove that the IP is usable, but reality is often harsh—this ideal is too perfect. In practice, when transitioning from one node to the next, you must optimize and improve in every aspect, such as power and signal integrity."

This makes IP management exceptionally difficult. "Solving IP issues is just one part," said Ranjit Adhikary, Vice President of Marketing at ClioSoft. Integrating various IPs also brings different challenges. For example, many IPs may have been considered for 10nm and 7nm processes, but different versions of IP can cause issues. Thus, during this process, comparisons between different IP versions are necessary.

Every new process node comes with significant uncertainties. Many chip manufacturers admit this is one of the biggest challenges in their work. However, many things are changing.

First, each new process node causes many factors to change, increasing the likelihood of errors.

Second, the market itself is constantly evolving. Many new fields are emerging, and these may follow entirely different development paths compared to previous ones like PCs, smartphones, and tablets. Adapting to these new trends is a major challenge. For example, the latest automotive developments differ from smartphones because they don't need to support functions like texting or searching.

The cost of falling behind is often very high. This is why software was initially designed to solve such problems—it can be updated and iterated faster, playing a crucial role because software changes are easier than hardware modifications. This is one reason why FPGAs are becoming increasingly popular, as their software can be altered.

The ability to modify software is especially important because many future semiconductor markets, such as autonomous vehicles, healthcare, industrial electronics, and artificial intelligence, are rapidly evolving. "These new markets often require different protocols and interfaces, and the multitude of these can pose many problems," said Kent Orthner, System Architect at Achronix. How to solve these problems? Simplifying the entire process through software is an effective method. Thus, many companies now hope to address similar issues through programmability, such as writing software into cars to enable new functions via algorithm updates.

One consideration is how much data to transfer to memory and how much to store locally. "Storing data locally requires significant storage space," said Kurt Shuler, Vice President of Marketing at Arteris IP. "When adding this data to memory, you need to decide whether it can be effectively utilized."

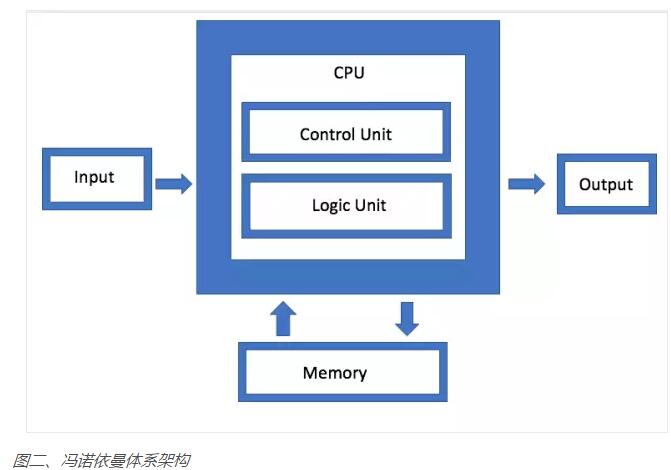

Therefore, generally, we don't send everything to memory. Instead, we use multi-level caches and proxy caches to transfer data from storage chips to different devices. Although these technologies are largely based on the von Neumann architecture, they can be considered a completely different version. The biggest difference is that we follow how data moves from a data perspective rather than considering software issues from the chip architecture. In reality, this data processing approach poses significant challenges for software-defined architectures but relatively minor ones for chips.

Security

On the other hand, a new factor influencing effectiveness is security. Compared to hardware, software often requires a very rigorous architecture to achieve security. Additionally, software can be remotely hacked over networks, increasing costs. This is why software remains constrained to some extent.

Various technologies can be employed to ensure chip security. The issue is that many companies are unwilling to invest heavily in chip security. Many manufacturers only consider adding security features to new chips when their chip security is threatened.

Aart de Geus, Chairman and CEO of Synopsys, agrees with this view. "This is a complex issue," he said. "Security often involves both hardware and software, but the biggest vulnerabilities often involve both. For many companies, this is difficult to understand and a novel problem. Looking at today's hackers, you'll find their techniques are sophisticated. There are many ways to address security. First, we can establish security barriers at the system level to ensure security, at least making the system adhere to security rules. Second, security can also be achieved through hardware. Among the clients we work with, many have invested heavily in software to build security. However, we also find that a single company cannot change the entire landscape; standardized approaches are still needed."

Nevertheless, security has become one of the factors to consider in software-driven design.

Automation Tools

From an engineering perspective, many objectives remain the same. Regarding Moore's Law, the primary goals are smaller, faster, lower cost, and higher performance. Among these, high performance and smaller size are two factors that will never change.

As Moore's Law gradually slows, the real challenge is economic viability, which EDA companies see as a significant opportunity.

"Sometimes, small architectures can achieve surprisingly good results in performance and power consumption," said Dave Kelf, Vice President of Marketing at OneSpin. "This is similar to how high-level synthesis tools can sometimes make a difference. Such tools can change the design cycle, freeing up more time from design to achieve better performance."

On one hand, this approach effectively meets the demands for new processes. On the other hand, faster tools and better training in their use can reduce the time and money spent on design.

Conclusion

In the short term, Moore's Law will likely survive, at least down to 5nm or even lower. However, its progress is becoming slower, more difficult, and costlier, increasingly misaligned with the demands of many specific markets.

More and more solutions require specialized designs for specific markets, such as different architectures and software-defined components that may be better suited to certain markets. The era of "one size fits all" is over. Universal designs in the semiconductor field are becoming less relevant for specific markets.

Note: All images in the article are from the internet and will be deleted if infringement occurs!

Hot News

Hot News